There’s a video at the bottom if you prefer to watch instead of read!

If reading is your thing and you want to learn, here you go…

As you know, turning a bunch of random information into a clinical pathway or decision-making tool is a bit complex. This is a good starting point for anti-obesity medications.

Due to the heterogeneity of obesity, and limited data treating it, predictors of response to anti-obesity pharmacotherapy treatments are not well established. Currently selecting the most appropriate anti-obesity medication for an individual patient is predominantly based on clinical experience. This is a simple algorithm that works pretty well:

1. Criteria

The FDA has criteria for the use of anti-obesity medications. The two essential criteria we have to know are criteria based on BMI and criteria based on age. Although we can use medications off-label (and we do it in medicine all the time) we need to color within the lines as much as possible when treating obesity.

There are a lot of charlatans in this space who are not following guidelines and with the sheer number of people affected by obesity and the demand for pharmacologic therapies, that number is just going to keep increasing.

Staying on the right path and following evidence-based guidelines is not only going to keep us out of trouble, but it will also keep us from being classified with all of the other money-hungry people out there trying to capitalize on an already vulnerable population.

All individuals (regardless of their BMI or age) are candidates for an intensive lifestyle intervention or a prescriptive nutritional intervention. Everyone can benefit from a healthy diet, good physical activity, good mental health, etc.

Individuals are candidates for anti-obesity medications when they reach a body mass index of 27 with comorbidities, or a body mass index of 30 regardless of comorbidities.

Keep in mind: that is for initiation of anti-obesity medications. During treatment, many patients will either send their comorbidities into remission and/or drop their BMI below the threshold. We need to look at this and use judgment. If someone gets their blood pressure under control using an antihypertensive medication, we don’t immediately remove the medication, claiming that it’s no longer necessary. The same thing applies to anti-obesity medications. If they are part of the process that gets that person to a healthier state of being, the minute they cross that threshold, we don’t remove the medication.

We need to use shared decision-making to figure out if the patient is ready to start weaning from the medication gradually – with the idea that it may need to be restarted immediately or sometime in the future to prevent relapse. When using medication this way, it should be documented appropriately.

The FDA also has criteria based on age. Children aren’t miniature adults, after all.

These are the ages for which the anti-obesity medications are FDA-approved:

- ≥12 yo: Phentermine/Topiramate ER, Liraglutide, Semaglutide, Orlistat

- ≥16 yo: Phentermine

- ≥17 y/o Diethylpropion, Phendimetrazine

- ≥18 Naltrexone/Bupropion XR

None of our anti-obesity medications have an upper limit of age for use, however, clinical trials have not enrolled large groups of patients over the age of 65. As with all patients, we need to consider concomitant disease states, drug interactions, and renal function before prescribing medications,

In addition to federal guidelines, most states have specific regulations regarding anti-obesity medications. We may or may not agree with these regulations, but to protect our license, we must adhere to them. Missouri doesn’t have many regulations at all, but Kansas is somewhat strict about using anti-obesity medications that contain controlled substances.

The Kansas Board of Healing Arts requires clinicians prescribing these medications to personally examine the patient every month, documenting an exam and vital signs, and restricts prescriptions to 30 days, without refills. The Board also states that the clinician cannot continue prescribing the medication if the patient does not lose at least 5% of their starting weight after the first 90 days of treatment.

It’s always good to know the rules when your ability to keep practicing hinges on following the rules!

2. Contraindications

Before making a choice about which anti-obesity medication is the best one for the patient, we always have to make sure and rule out any obvious contraindications. You can do this however you feel comfortable. When bringing up the discussion with patients,it’s helpful to organize the medications into buckets and cross off any obvious contraindications as you are talking with them – just to take them out of the decision-making process.

Now this isn’t really a contraindication, but it’s a caution. Although the AOMs are pretty safe drugs, they definitely scare some people. We should always be cautious and careful when prescribing medications, but fear and/or ignorance should not be a reason to avoid prescribing them altogether. Having obesity, especially severe obesity, carries a big risk of morbidity and mortality, not to mention a decrease in quality of life. The risk of not treating this disease typically justifies the risks associated with treatment.

Most of the AOMs have the potential to elevate blood pressure. The average elevation in blood pressure with these medications is minimal – but not unheard of. If someone has uncontrolled HTN or presents to the office without a diagnosis of HTN and has a significantly elevated blood pressure, they should not be prescribed one of the AOMs that can elevate blood pressure until the underlying HTN is evaluated and controlled.

Every time you prescribe a new AOM, review the medication in depth with them. If they have a diagnosis of HTN or suspected mild HTN, give them the handout about blood pressure and medication monitoring.

All of the anorectic medications (heck, most medications) can prolong the QTc interval. Because it is painless, takes only a few minutes, and costs almost nothing, it’s good practice to perform an EKG and check their QTc interval before starting patients on an anorectic medication.

If someone has a QT interval in the borderline range, they are usually going to reverse it quickly with weight loss, which will improve their overall health, so it’s not usually necessary to withhold meds in this case. However, working with them to make sure they know how to reverse the QT interval and making sure it gets reversed within a month before continuing them on the medication is good practice.

What follows is a summary of the major contraindications and warnings/precautions for commonly prescribed AOMs. This is by no means comprehensive. As with all medications, you should thoroughly review the manufacturer’s prescribing information and the reports from the studies used to obtain approval.

Anorectic Medications (Phentermine, Phendimetrazine, Diethylpropion)

- Contraindications: known allergy or hypersensitivity, pregnancy, nursing, history of CVD (CAD, stroke, certain arrhythmias, CHF, uncontrolled HTN), hyperthyroidism, narrow-angle glaucoma, agitated states, history of drug abuse.

- Warnings/Precautions: avoid concomitant use with other stimulants, elevations in heart rate and/or blood pressure due to anorectic medications are typically very minimal, however, blood pressure monitoring in anyone with HTN is recommended.

Phentermine/Topiramate ER

- Contraindications: known allergy or hypersensitivity, pregnancy, nursing, history of CVD (CAD, stroke, certain arrhythmias, CHF, uncontrolled HTN), hyperthyroidism, narrow-angle glaucoma, agitated states, history of drug abuse, .nephrolithiasis, concomitant MAOI use within 14 days.

- Warnings/Precautions: pregnancy testing is recommended before initiation and monthly during therapy. Women who can become pregnant should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus and to use effective contraception during therapy, titrate QOD dosing for at least 7 days if discontinuing the med from 15/92 mg dose to reduce seizure risk, avoid concomitant use with other stimulants, may potentiate hypokalemia caused by non-potassium-sparing diuretics, may potentiate CNS depressants such as alcohol, use caution in people with renal impairment.

Naltrexone/Bupropion XR

- Contraindications: known allergy or hypersensitivity, uncontrolled HTN, seizure disorder, narrow-angle glaucoma, bipolar mood disorder, anorexia nervosa or bulimia, undergoing abrupt discontinuation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and antiepileptic drugs, use of other products containing bupropion, chronic opioid use, during or within 14 days of taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

- Warnings/Precautions: pregnancy was removed as a contraindication in 2020, however, the prescribing information recommends discontinuing when pregnancy is recognized. Can cause false positive urine test results for amphetamines, tamoxifen and digoxin levels may be decreased, use caution in people with renal impairment.

Peptides/GLP-1 Agonists (liraglutide, semaglutide, tirzepatide)

- Contraindications: known allergy or hypersensitivity, pregnancy, nursing, personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia syndrome type 2.

- Warnings/Precautions: acute pancreatitis, including fatal and non-fatal hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis, has been observed. Discontinue promptly if pancreatitis is suspected; do not restart if pancreatitis is confirmed, causes dose-dependent and treatment-duration-dependent thyroid C-cell tumors at clinically relevant exposures in rats and mice. Monitor heart rate to evaluate for possible heart rate increase, renal impairment has been reported post-marketing, usually in association with dehydration, monitor for depression or suicidal thoughts and discontinue if symptoms develop, consider reducing the dose of concomitantly administered insulin secretagogues or insulin to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia. Delaying gastric emptying has the potential to impact the absorption of concomitantly administered oral medications. Monitor patients on oral medications dependent on threshold concentrations for efficacy and those with a narrow therapeutic index (e.g., warfarin) when concomitantly administered. Advise patients using oral hormonal contraceptives to switch to a non-oral contraceptive method or add a barrier method of contraception for 4 weeks after initiation and for 4 weeks after each dose escalation. Hormonal contraceptives that are not administered orally should not be affected. Be cautious in people with gastroparesis.

3. Combination therapy

Combining a prescriptive lifestyle intervention (including a prescriptive dietary intervention) with a pharmaceutical intervention is considered combination therapy. The treatment of most diseases is some sort of combination therapy.

Sometimes we have to deploy multiple medications. Two of our current AOMs are combination therapies already. Obesity is a disease affecting multiple pathways and may require multiple interventions to maximize outcomes. As with other chronic disease management strategies, combination therapies will likely produce more weight loss than single agents alone.

When possible, it’s also judicious to try and target two different disease states with one medication, thereby potentially minimizing the amount of medication a person takes. Patients who already have a diagnosis of T2DM may benefit from using a GLP-1 RA and metformin – because those drugs will treat both obesity and diabetes. Someone with a history of migraine headaches could benefit from topiramate. Someone with depression could benefit from Contrave.

4. Cues

Cues focuses on symptoms and side effects, i.e. cues that may help predict the response to medication. For example, if a patient experiences hunger mainly in the evening, using a medication with a sustained effect is preferred over shorter-acting medications. Cues can also refer to patient preference in frequency and route of administration. If a patient struggles to remember their medication, once-weekly dosing may be considered over once-daily dosing. Once-daily dosing would definitely be preferable to twice-daily dosing.

Cues can also be listening to current symptoms that might be aggravated by a medication’s side effect profile. For example, if a patient struggles with insomnia, a more activating medication may exacerbate the symptoms.

Cues also means precision medicine. Obesity is a heterogeneous disease. The current anti-obesity medicines on the market target a wide range of pathways in the body. For every treatment, there are hyper-responders and non-responders. Until we have better data or pharmacogenetics, can we leverage our experience? This is one of the reasons to take a detailed history.

As with every field of medicine, there are patterns in Obesity Medicine. We don’t have a perfect system of organization, but what follows is a simple way to organize and assign the treatment to the patient quickly and without unnecessary complexity. Patients tend to be grouped into one of three phenotypes. Some have features of more than one and some have all three.

External Noise

When asked what drives them, many people state that it has to do with food cravings. Some people spend a lot of mental energy fixating on specific foods. People who complain about food cravings feel like there’s an external voice (inside their head) that doesn’t really belong to them that is constantly talking about food. They have intrusive thoughts about food and often engage in impulsive eating. People with this phenotype are constantly thinking about food and engaging in foraging behavior. People with food cravings often say “I just love food”. They often have dysregulated eating (a natural consequence of having something front of mind all the time). They are easily distracted by food cues. They can eat a normal amount of food at a meal and feel satisfied initially, but begin thinking about food within an hour after eating. They often have to eat something to get themselves to sleep, and they typically wake up hungry in the morning. Food truly rules the world.

A prescriptive dietary intervention is always the primary treatment methodology for this. Getting adequate dietary protein and minimizing simple carbohydrates and sugars helps these people significantly as it balances out the insulin/glucose response.

There’s a lot of lifestyle intervention that needs to be done as well.

When choosing anti-obesity pharmacotherapy, patients who tend to be very sensitive to external noise often do best with our anorectic medications. Qsymia, phentermine, phendimetrazine, and diethylpropion tend to work very well in these patients. The peptides work as well, but whenever possible (when there are no obvious contraindications), it’s best to try a more cost-effective medication first. There are a lot of hyper-responders to the anorectic medications.

Internal Noise

People with a great deal of internal noise use food to soothe their emotions. More often than not, these people know the drive to eat is coming from their own brain – and that it’s typically in response to feelings or emotions. That void might be emptiness or boredom. It might be sadness or guilt or another negative emotion. It might be stress or overwhelm. Reward eating typically fits best in here as that’s an emotional drive – to want to be rewarded for doing something of value. People who are primarily driven by this internal noise find food as the solution to something unpleasant.

Although these people are foraging for food, the drive is less specific than the people with cravings. These people can wander to the pantry repeatedly and sample a variety of items, looking for the right fit. When improving their diet, they can eat a normal to a large amount of meal and still report feeling hungry, although when you dive deeper into it, what they really mean is that they are “unsatisfied” – it’s not actually physical hunger, it’s that the meal hasn’t done its thing emotionally.

People driven by these internal cues often reported an intense desire to eat after work or in the evening. Similarly, they often find it fairly easy to adhere to healthy eating in the morning and early afternoon, but it deteriorates through the late afternoon into the evening. They wake up the next morning determined that the pattern isn’t going to repeat itself. For some people, this pattern is shifted – the weekdays are easy and the weekends are hard. Either way, the on-again off-again idea is consistent.

This variant of emotional eating can coexist with using alcohol, but it doesn’t have to. Some of these patients may avoid alcohol and rationalize to others that eating is a “better option” than drinking. They know they are using it in a similar manner as people who use alcohol for reward.

Again, a prescriptive nutritional intervention is designed to do everything physically possible to help with these things. Adequate dietary protein is important and giving access to a lot of savory foods rich in healthy dietary fats can help.

A lifestyle intervention is also essential.

In terms of pharmacotherapy, people that are emotional eaters tend to do very well with Contrave. They also will typically respond to the peptides, but again, when using step therapy, starting with Contrave (if it’s not contraindicated) is the best first choice.

Culture

There are some bigger, more pervasive, more universal issues that patients report frequently that are lumped under culture. Those don’t seem to be phenotypes that respond to medications. They are more cultural, pervasive mindset issues that require mindset work which is a huge part of a lifestyle intervention.

5.Cost

Obesity treatment doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Preventing and treating obesity may help lower healthcare costs someday, but it’s a delicate balance and it hasn’t come to pass yet. The good news is that we don’t have to do amazing things to achieve health benefits. Almost all physical conditions improve significantly with 5% weight loss. In fact, 5% weight loss is considered a benchmark for effective obesity treatment. With the recent AOMs on the market delivering significantly more, this definition may be shifting, but most coexisting chronic diseases get significantly better with a 5% loss.

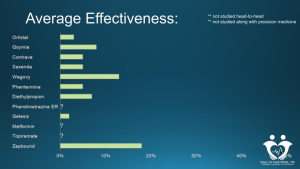

What follows is a graph showing the published effectiveness of the various anti-obesity medications. These are derived from individual studies and have not been studied head-to-head. The duration and patient populations vary as well – but in a general sense, this is what they look like when put out there as a type of “menu”. Keep in mind that most of this data (especially data about the newer medications) comes from pharma-funded studies, which means the study participants have lots of support and very little friction during the trial. It’s much easier to stay engaged when most of the barriers are removed – including access and cost.

This goes way beyond the scope of this article, but it’s also important to realize that all of these studies are based on calorie restriction as the basis of achieving weight loss. All of them involve teaching patients to achieve a caloric deficit, which, predictably, eventually, triggers physical hunger. What this graph tells me is that anti-obesity medications vary in their ability to suppress physical hunger. When that is the primary driver, they definitely have a wide variety of effectiveness. However, if we can fix physical hunger via prescriptive dietary intervention, we only have to work on food noise.

The effectiveness of suppressing food noise is all over the map in terms of these medications (when we are using them that way – not trying to suppress physical hunger). Most of them do a very good job for most people of quieting that food noise.

And cost is important. Some of our anti-obesity medications are incredibly inexpensive. The oral medications are all less than $100 a month. If someone takes these for a full year, the maximum out-of-pocket cost is going to be $1200. These newer anti-obesity medications cost somewhere between 1000 and $1400 every month. This means that a years worth of therapy can easily reach $20,000. For one person. We cannot spend $20,000 per person per year to head off this obesity epidemic. Implemented at scale, it would quickly break the healthcare system as a whole.

Although we all like to grumble that insurance should cover everything we want it to cover, it’s important to realize that insurance companies don’t contribute anything to the cost of care. They simply act as money exchangers – taking money from those paying into the health plan (for commercial plans, this is the employers and the people employed by them and for government-funded plans, this is the taxpayers), skimming some (a lot) off the top to cover administrative expenses, and then sending that money to those performing the services.

When the cost of healthcare goes up, the insurance companies simply take more money from those paying for it in the first place – which is mostly individual people (they just don’t realize it). When employers are required to shell out more money to cover their portion of the health plan, they have to take it from somewhere. It usually comes from money set aside for raises or new hires, so individuals pay for it indirectly.

As clinicians, we have an ethical responsibility to be good stewards of healthcare dollars. When the cost of healthcare rises, people suffer. And those with the fewest resources typically suffer the most.

The other thing we have to think about to keep costs down is the overall framework. We need to get the appropriate people into treatment. Although some people may spend a great deal of emotional energy thinking about their weight and physical appearance, they may not have cardiometabolic disease and/or excess weight. If their BMI isn’t 30 (or 27 with cardiometabolic comorbidities) they don’t qualify for obesity treatment. We can focus on prevention – and we should. All of those lifestyle interventions can be great for prevention, but prevention and treatment are different. If they have issues with body dysmorphia but are metabolically healthy, a referral to a therapist will probably do these people more good than a prescription.

If they do qualify for obesity treatment, they need to be willing and able to implement an intensive lifestyle intervention. If they aren’t, adding pharmacotherapy is not the right idea. We need to focus on readiness to change until the person is ready to implement an intensive lifestyle intervention. If they are ready, it’s time to move into step therapy.